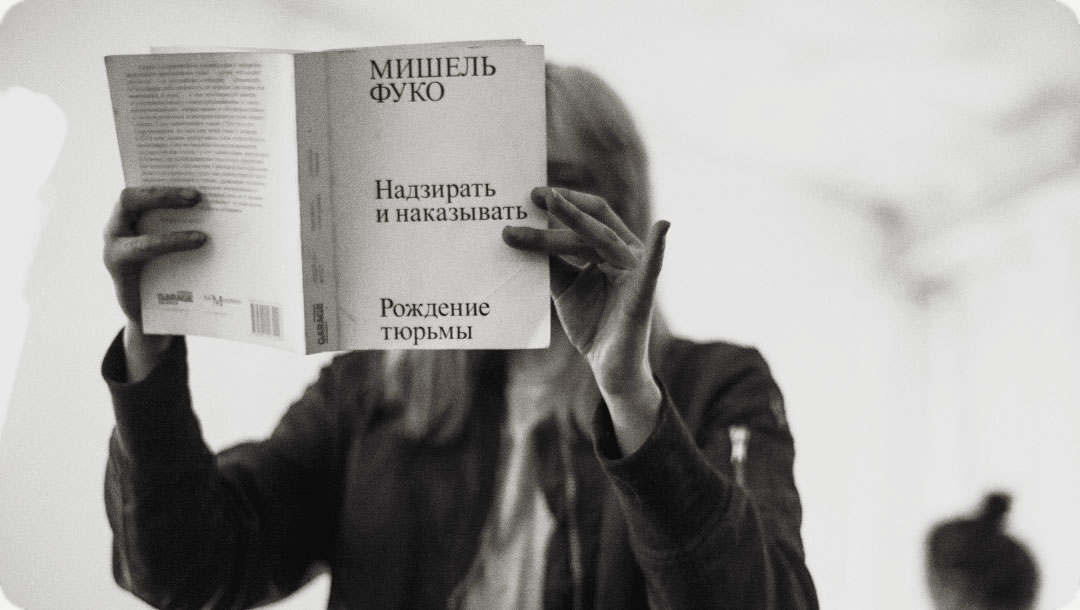

Another seller might have said: «Excellent choice!» Prosecutors, during an inspection at the most famous—but far from the only—Moscow intellectual literature store «Falanster», seized several books by Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag, and «Discipline and Punish» by Michel Foucault.

Another seller might have said: «Excellent choice!» Prosecutors, during an inspection at the most famous—but far from the only—Moscow intellectual literature store «Falanster», seized several books by Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag, and «Discipline and Punish» by Michel Foucault.

Once again, the fates of Arendt and Benjamin strangely rhymed. The last time Arendt's biography was of interest to competent authorities was in 1940–1941 during a multi-stage escape from France to Spain and Portugal, followed by a journey across the ocean to New York. She traveled more or less the standard route for those fleeing the Nazis and their Vichy regime colleagues in France. The outstanding Jewish-German poet and essayist Benjamin, to avoid deadly deportation from France to Germany, took the same route somewhat earlier. He had a special American visa, which his colleagues from the Institute for Social Research, relocated from Frankfurt (hence the term Frankfurt School) to Paris, and then, very timely, to New York, secured for him. There was also a Spanish transit visa to the refugee-saving Lisbon, to the gates of the ocean, to the Statue of Liberty. But there was no exit French visa, which, as Arendt wrote in her essay on Benjamin in the «New Yorker», «was still required at that time and which the French authorities invariably denied to emigrants from Germany to please the Gestapo».

The escapees knew of a road through the mountains, not guarded by French border guards, leading to a border town called Portbou in Catalan (Port-Bou in French). For Benjamin, who suffered from heart failure, this crossing was particularly difficult. And it was precisely on the day of his arrival that Spain closed the border and did not accept visas issued in Marseille. As Arendt wrote, «emigrants were offered to return to France the next morning by the same route. That night, Benjamin took his own life, and shocked by his suicide, the border guards allowed the remaining to proceed to Portugal. And a few weeks later, the entry ban was lifted». This happened in September 1940, and in January 1941, the same road, opened thanks to Walter Benjamin's suicide, was taken by Hannah Arendt and her husband Heinrich Blücher. Ten years later, her famous work on the nature of totalitarianism would see the light. Was it this that interested the Russian inspectors who came to the bookstore?

Susan Sontag's bisexuality might attract the competent authorities, but in itself, it is not propaganda of «incorrect» orientations, not to mention that this is reading for ultra-intellectuals. In the case of Michel Foucault, it seems the interest was sparked by a book whose title could be seen not as propaganda of the philosopher's sexual orientation, but as an analysis of the professional sphere of law enforcement. Although «Discipline and Punish» is a book about biopolitics and biopower, about the management of the human body in a disciplinary society, a society of surveillance. «Panopticon» is a system of total surveillance, allowing the overseer, while remaining invisible, to monitor prisoners. It was described by Michel Foucault. And in it, one can see a metaphor for the type of state that claims power over the bodies of its subjects and has been formed over a quarter-century of one man's rule in the country where the «Falanster» store is located.

Strictly speaking, if anything is to be seized, it should be the entire array of intellectual literature, because at its core lie thought and doubt, which are, in turn, the foundation of human culture and humanism. That which makes a person human and distinguishes them from earlier stages of primate development.

As V. I. Lenin used to say, «one can become a communist only when one enriches one's memory with the knowledge of all the riches that humanity has produced». But from the perspective of today's censors, overseers, and ideologues, in this situation, one can become not so much a communist as a liberal.

This position is also taken by voluntary informers, thanks to whom the authorities are paying more and more attention to the book market, the book trade network, and libraries. They seem too free, which displeases all leading figures—from the new comrade Fadeev, the secretary of the Writers' Union Medinsky, to the president's cultural advisor Yampolskaya. It's not enough that stores do not risk selling books by «foreign agents», libraries do not lend them out, and publishers do not sign contracts with them. It's not enough to cancel book presentations at a call from above or the side, from concerned rioters. (In the same «Falanster», more than a month ago, the presentation of the book «Antifascism for All» was canceled; before that, several venues canceled presentations of Nina Khrushcheva's book about Nikita Khrushchev, and these are just two examples out of many.) A more fundamental control is needed. It is necessary to «Supervise and Punish».

However, there are too many good books describing authoritarian and totalitarian power and their ideology. Works of past eras do not age and provoke inevitable allusions. Not only has Orwell's «1984» remained a bestseller throughout the entire SVO, as have the now popular novels by Remarque in the book trade network, which were the first to be burned by the Nazis when they came to power. The book market is experiencing a boom in publications of allusion literature about everyday life in 1930s Germany, about the causes and consequences of the German catastrophe, and about the details of entry and exit from it. Only in recent months have stunning translated works by Uwe Wittstock «February 1933. The Winter of German Literature», Friedrich Meinecke's «The German Catastrophe», Thomas Mann's «Listen, Germany», Harald Jähner's «Wolf Time. Germany and the Germans: 1945–1955» been released. Finally, the diaries of Victor Klemperer (1933–1945), an insider researcher of the Third Reich's language regime, have just seen the light. Publishers, in the end, are not to blame that everyone finds endless allusions in these and numerous other works. And what to do with long-published and actively reissued, including in cheap paperback editions, classic works like Erich Fromm's «The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness». All this can be quoted for miles.

The nature of the interest of censors, ideologues, and informers in literature of a certain type exposes the authorities completely. They fear self-exposure. They recognize themselves in the classics. And their ultimate goal is clear, their tasks defined. This was written about by the very same Hannah Arendt, who fell under suspicion—almost half a century after her death: «Totalitarianism in power inevitably replaces all first-rate talents <...> with fanatics and fools, whose lack of intellectual abilities remains the best guarantee of their obedience».

Evil is banal, it comes in the guise of boring bureaucracy with two phrases on its lips—«I was following orders» and «I have a mortgage». All of this is written about in books—the source of knowledge.

* Andrey Kolesnikov is considered a «foreign agent» by the Ministry of Justice of the Russian Federation.